Coming Up

-

CVP: Upcoming Courses

30 Apr 24 @ CVP: Various

-

MPTS 2024

15-16/05/2024 @ Olympia, London

-

KitPlus Show

18 Jun 24 @ SEC, Glasgow

Sponsor News

Who do the top wildlife film-makers really admire?

It's always interesting to hear who the experts in any field revere. In yesterday's Guardian, Emine Saner asked five top wildlife-filmakers to nominate their favourite living artist in their field. The answers are below. See the original article on The Guardian online

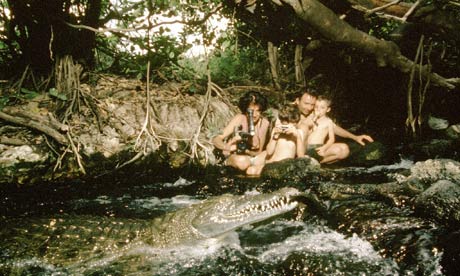

Alan Root on Mark Deeble and Victoria Stone

Mark Deeble and Victoria Stone have produced an unbroken string of great wildlife films, notable for the variety of creatures depicted, the strange behaviours captured, and the stunning photography – but most of all for the quality of the storytelling. Giant crocodiles stalk their prey; hippos open their mouths to have their teeth cleaned by schools of fish; tiny wasps hatch into the extraordinary world hidden inside a fig; a fish opens her mouth to release tiny fry, not realising she has been cuckolded, and they are someone else's young. They have brought so many new, extraordinary sequences to the screen, all of them woven into deeply satisfying stories. And that, for me, is the raison d'etre for film-making.

Alan Root's 1978 film about termites, Mysterious Castles of Clay, was nominated for an Oscar.

Gavin Thurston on Martin Dohrn

Dohrn's technical innovations are inspiring. The lens systems he designs and builds might look very Heath Robinson, with all their buttons and dials, but they serve a purpose: they have allowed us to see new behaviours in the wild. Using military technology, he came up with the Starlight Camera, allowing him to capture animal behaviour in the wild in complete darkness, for a film called Mara Nights, shot in a Kenyan national park. As soon as you turn a light on, nocturnal animals change their behaviour. But film in the dark and you'll see things you'd never normally witness.

Film cameras are generally so huge, you can't follow something such as an ant. So he built a miniature one, called an "ant cam", that lets you shoot at knee level. It was like having a camera in a tiny helicopter. Rather than being stuck in one position, suddenly you could do tracking shots around army ants, or follow them through the rainforests of central America.

Gavin Thurston worked on the BBC's Life in Cold Blood and Planet Earth.

Sophie Darlington on Doug Allan

Allan is one of those people who goes beyond the call of duty. The results are extraordinary and inspiring. He did a lot of work on Blue Planet and Frozen Planet. When he became one of the first cameramen to dive under the Arctic ice, I thought: "I couldn't do that." He brought us images we'd never seen before: his footage of sea stars feeding under the ice was not only beautiful but a revelation, too. It showed the seabed as such a hostile environment.

One of his standout sequences is of a polar bear trying to capture beluga whales in Blue Planet. It is extraordinary, in such extreme conditions, to capture this kind of behaviour: their scars; the bear's jump. It's never been filmed before. But then he's always pushing his work to the next level. He has filmed polar bears and killer whales a number of times, actually, but each time he goes back he will use a new technique, or look for new behaviour, so his work's always fresh.

Sophie Darlington has worked for the BBC, National Geographic and the Discovery Channel.

Charlie Hamilton James on Hugh Miles

I was nine when I saw Miles's On the Tracks of the Wild Otter. It changed my life. It didn't just turn me into a cameraman, it made me an otter-obsessive. The best wildlife cameramen put in a huge amount of time, and he puts in more than just about anybody – to the point where the animals trust him. He is profoundly patient. Sometimes his films take years to make. With that patience come those amazing moments other people would miss. He filmed polar bear cubs emerging from their den in the Arctic: to get shots like that takes weeks of waiting – in freezing conditions. And when those moments finally happen, he has the skill and level-headedness to film them beautifully.

Charlie Hamilton James's films include My Halcyon River for the BBC.

Doug Allan on Alastair MacEwen

MacEwen shoots in all kinds of ways: he can do long lens work, say, in the African savannahs, as well as macro footage, closeup stuff likeinsects, rats and mice. Unless you're working in the desert, you just don't see animals like that scurrying around, so you need to build sets. That takes skill: you need to look after your animal so it accepts your set as its natural environment and will carry on displaying the behaviour you want. He is very good at building – and lighting – sets.

He has been principal cameraman on a lot of David Attenborough series. I remember he filmed some archer fish in the Amazon that use spit to shoot insects off branches and down into the water. It was covered from lots of different angles – and in slow motion. He is quite a technical man. He takes the latest technology, wrestles it to the ground, and comes back with amazing pictures.

Doug Allan worked on BBC's Blue Planet and Frozen Planet.

Where to next?

Coming Up

-

CVP: Upcoming Courses

30 Apr 24 @ CVP: Various

-

MPTS 2024

15-16/05/2024 @ Olympia, London

-

KitPlus Show

18 Jun 24 @ SEC, Glasgow

Sponsor News

GTC on Facebook

.jpg)